China faces significant challenges in upgrading its workforce, as an unequal education system holds the country back despite its coordinated national policies and ambitious goals, witnesses testified on Friday at a top US congressional advisory commission on China policy.

At a hearing to assess China’s challenges and capabilities in educating and training its next generation of workers, witnesses said the US should attract top talent from China, integrate emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) into pre-university education and federal hiring standards, and help small businesses bring new technologies from the lab to the market.

But even if Washington did not change its policies, the US should retain its lead in science and technology, according to George Washington University political scientist Jeffrey Ding. “Sometimes the status quo is a defensible policy option,” he testified.

The hearing was organised by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC), an independent panel set up by Congress in 2000 that reports directly to lawmakers about the national security implications of the bilateral relationship in trade and economics.

The testimony came as the US explores options to elevate its economic competitiveness and diversify its supply chains away from China. It also coincided with China trying to build a more efficient, high-quality workforce to cope with the challenges posed by its ageing population.

China’s nearly 1 billion-strong working-age population peaked in 2014. By 2100, China’s workforce is projected to number fewer than 400 million people, according to UN data from July.

And by 2030, up to 220 million Chinese workers may need to switch occupations due to automation, according to a 2021 report by McKinsey, a consultancy.

Witnesses on Friday spoke in agreement that China’s improved labour productivity was increasingly dependent on educational advances.

While high school students in economically advanced Chinese provinces have ranked first internationally in science and maths, there is a “moderate size gap” domestically between urban and rural students, according to testimony from Prashant Loyalka of Stanford University.

The rural-urban divide was significant as rural students comprise two thirds of students in China, witnesses said.

And while Chinese students may be entering university with higher levels of achievement compared to their peers abroad, they showed little progress in basic academic skills and critical thinking over the course of their studies, Loyalka added.

After four years of study, Loyalka contended, graduates in China have “comparable levels” of major-specific and critical thinking skills as graduates in India and Russia, but they are “considerably lower” than those of US-based graduates.

Witnesses agreed that the sheer number of students in China could not be overlooked: 18-to-24-year-olds in China’s four-year undergraduate programmes outnumber their counterparts in the US by eight million.

That said, China could still grapple with the middle-income trap, a point where income stagnates below the wage levels of highly developed economies.

Scott Rozelle, also a Stanford academic, testified that China had one of the lowest levels of human capital in the middle-income world, lower than Turkey, South Africa and Mexico.

Students in rural areas faced low-quality teachers, nutritional deficiencies, mobility restrictions and a stratified higher education entrance process that has increasingly emphasised creativity and innovation, favouring better-resourced urbanites, witnesses said.

The biggest problem, Rozelle said, was the lack of a “quality home environment”. This has led to high rates of cognitive delay in young children.

China was aware of these challenges, witnesses said, noting the country had substantially boosted investment in rural education and vocational training to promote the development of its workforce.

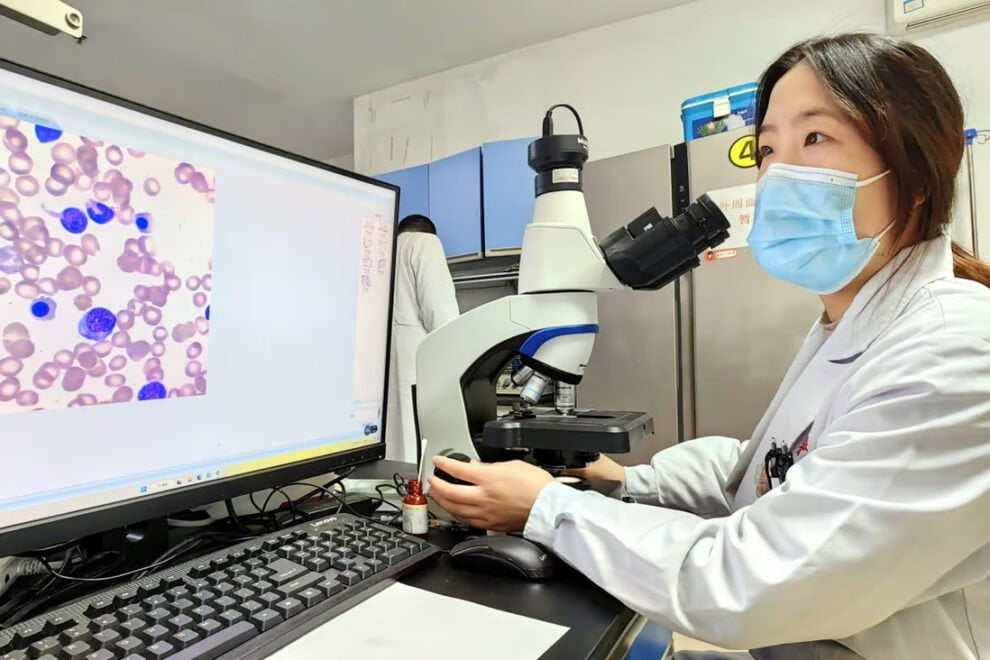

Beijing has also invested extensively in research and development and developing higher education overall, especially in pushing a standardised AI curriculum. More than 440 Chinese universities have AI-related majors, according to Dahlia Peterson, a Georgetown University researcher.

However, AI programmes are producing many graduates who do not fit industry needs, witnesses said. Nor have vocational training programmes contributed much to improve China’s human capital development.

An examination of unique aspects of the Chinese systems helps one understand the country’s competitive potential vis-à-vis the US, witnesses said.

China’s science and technology system was “more interconnected and holistic than the US system, blurring the lines between public, private, military and civilian”, testified Anna B. Puglisi, also of Georgetown.

She highlighted China’s “state key labs” system, which ties together government, academia and business to advance national priorities like AI and biotechnology.

Unlike Washington, Beijing can more easily set a national curriculum, prioritise and channel resources towards key technologies, and sustain investments over time without concern for changes in government and policy, Puglisi added.

“If we don’t continue to train our students, technicians, researchers, as well as invest in the tools of discovery we will not be able to keep pace,” she said.

Ding of George Washington stressed that instead of focusing on a country’s ability to innovate, more emphasis should be put on its “diffusion capacity” – the spread of innovations across the economy – especially for multipurpose technologies like electricity and computers that have historically contributed the most to growth.

“It doesn’t matter much which state produces the first ChatGPT or the first major breakthrough in artificial intelligence,” he explained. “It matters a lot more which state intelligentises its economy at scale.”

Ding said China’s innovation capacity was on par with the US, but that it was facing a “diffusion deficit”, noting a “wide gap between China’s ability to produce new technologies and its capacity to spread them across a lot of productive processes”.

And “party-planned economies and centrally planned economies are not good at diffusion”, he added.

This inability to modernise China’s economy could drive China’s most productive young workers to leave, some witnesses said, enabling the US to benefit.

It would be in America’s long-term advantage to welcome China’s young people, who “largely maintain a positive image” of the US as a land of opportunity, freedom, and democracy, testified Zachary Howlett, an anthropologist at the National University of Singapore.

Source : SCMP